DHARMA TALKS BY ZEN MASTER SENSHIN

Khacho Yulo Ling Buddhist Centre Cairns

|

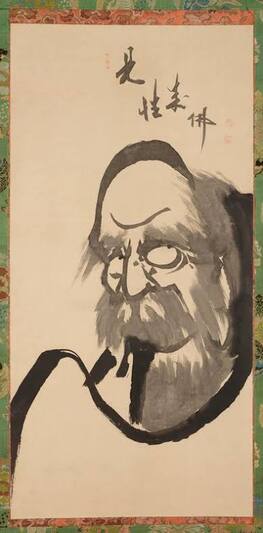

In the fifth century in India, Bodhidharma received transmission from his teacher, Prajnatara, who asked him to go to China to teach.

Bodhidharma was 28th in the Buddha’s patriarchal lineage. So, when he went to China, Bodhidharma became the first Ancestor in China. There are several important stories that are attributed to Bodhidharma and how his teaching shaped not only the Zen traditions and lineages, but other Mahayana traditions as well. It has also been said that Bodhidharma lived in a cave in Northern China at a Shaolin Kung Fu temple for nearly a decade.

One of several recorded encounters that Bodhidharma had was with Emperor Wu. This occurred soon after Bodhidharma’s arrival in Southern China. Emperor Wu was an avid Dharma supporter. He did everything his position of power allowed to support monks, nuns, and laypeople. He oversaw, and provided resources to build temples to help Buddhism take hold in Southern China. Certainly Emperor Wu would have heard of this stranger coming from India, someone who was the real deal, and who had received transmission in the Buddha’s lineage. Bodhidharma met Emperor Wu as he travelled through China. The dialogue between these men has been recorded in both the Blue Cliff Records (Case #1), and in the Book of Serenity (Case 2), two compilations of koans used in Zen traditions. This famous encounter is said to have gone like this:

When Emperor Wu had finished describing his considerable efforts in support of the Dharma he asked:

“What merit have I achieved?”

Bodhidharma replied, “No merit.”

Taken aback, Emperor Wu then asked,

“What is the highest meaning of the holy truths?”

Bodhidharma said, “Empty, without holiness.”

Perplexed, Emperor Wu questioned,

“Who is facing me?”

Bodhidharma answered, “Not knowing.”

Emperor Wu asked Bodhidharma what merit he had accumulated. Here he was having spent a great deal of money and having done everything he could to look after the form of the Dharma. He most likely felt pretty chuffed with himself. But Bodhidharma gave him a surprising answer, “No merit.” After all the hard work that you have done there is no merit. Of course Emperor Wu was taken aback as he saw himself as a great benefactor of the Dharma. He saw himself not only as a caretaker of the Dharma, but as someone who actually got it, who understood the Dharma, his “understanding“ manifested through his benevolence. Even in “doing good” this is how it is when we have ideas of who we are and those ideas are challenged. We become unsettled, confused, and filled with doubt. Our very ground of being is shaken to its core.

Emperor Wu persisted by asking, “What is the highest meaning of the holy truths?” By now, Bodhidharma saw Emperor Wu’s state of mind clearly as he replied, “Empty, without holiness”. Once again, Bodhidharma reiterated the truth; there is nothing – not one single thing. And Emperor Wu was perplexed. Bodhidharma’s insightful and skilful directness - the pointing directly to emptiness — was something he had never experienced. Still, he asked, perhaps in a state of shock, “Who is facing me?” To which Bodhidharma responded, “Not knowing.” What is there to know, and what is it that knows?

The Emperor did not get Bodhidharma’s teaching at all. It was not a question of Bodhidharma’s judgement of Emperor Wu, at least not in the way Emperor Wu would have imagined. Bodhidharma was looking for essence and there was none. Even in the donations Emperor Wu gave to the Buddhist community, there was no essence. Emperor Wu always wanted something in return. He wanted recognition, which was ego driven. I am doing this - what do I get in return? Emperor Wu’s ego driven existence was right there in his first question, “What merit have I accumulated?” For Bodhidharma, there would have been no reason to stay so he left and travelled to Northern China.

Emperor Wu was trying to do everything for the Dharma except the only thing that is important and beyond form, which was to see his true nature clearly, then clarify it and purify it until he became a Buddha himself. It is only from this deeply polished state of mind that we understand and practice true merit and actually help others. This is the notion of no merit - there is nothing to gain from making an offering. Offerings need to be given freely. Everything needs to be given in our zazen. Just give it all with no strings attached. Nothing!

The last part of this recorded encounter occurred after Bodhidharma had left the temple. The encounter was between Emperor Wu and a spiritual advisor who had heard of the encounter and asked, “Do you know who that was? That was the Avatar of the Buddha.” Emperor Wu asked him to send his fastest horsemen and to bring Bodhidharma back to his palace. But the advisor forewarned the Emperor, “Even if he sent the whole country, Bodhidharma could not be brought back.”

Emperor Wu realised with deep regret that he had missed the opportunity to be taught by the Avatar of the Buddha. After Bodhidharma’s death, he wrote a stanza for Bodhidharma’s monument:

“Alas, I saw him without seeing him.

I met him without meeting him.

I encountered him without encountering him.

Now, as before, I regret this deeply.”

Bodhidharma’s shaping of the Dharma, from a merging of Taoism and Mahayana Buddhism into Zen, and the effect of his direct teaching throughout the many Mahayana traditions, is beyond merit. In our traditions, we give him credit for being the father of Zen. At that time, Buddhism in China was just booming, many keen people were diving into the essence of Zen. After Bodhidharma’s life, his clear understanding was transmitted to his heirs. For example, in the records, the Fifth and the Sixth Patriarchs in China are right there in their understanding and pass that onto their successors; this ripeness, this aliveness.

There are a number of examples of how Bodhidharma helped to transform misunderstandings, misguided perceptions, and out-dated practices. But first, let’s look at Bodhidharma’s connection to the Shaolin temple. The Kung Fu community welcomed Bodhidharma’s teaching and either at his request or by the nature of his being, Bodhidharma was offered the opportunity to live in a cave on the temple’s property. While living in the cave, Bodhidharma sat for nine years and developed his incredibly clear and deep realisation - coming right from beyond his very source. He sat zazen and just as the Buddha had done, worked ceaselessly, purifying and clarifying his own mind. It is interesting that he did not come to Cairns to teach. He did not get lonely or want to go back home and visit his wealthy parents. He did not miss the special noodle dish with the lovely seafood that he used to eat. He did not miss anything. Not one single thing. This is the Avatar of Buddha who came and sat in a cave and it was his students who sought him out there.

There is another recorded encounter about the awakening of Bodhidharma’s first disciple Hui K’e and the trials he experienced as he sat outside the cave in the winter, waiting to be admitted. The tradition of waiting outside a temple’s gate, or in an outer building to test students’ resolve still continues today in some temples and monasteries in Asia. Bodhidharma tested the handful of people that found him – those that had a karmic connection with him. He tested their resolve. There it is right there in the Zen tradition, this testing of someone’s resolve. Are you here in order to follow ideas that you have so that you can confirm them as egoistic accomplishments? Or, are you really here to do the work? Are you really here to let it all go? Are you really here to die completely? That is the point of zazen – to experience directly your own true nature, not just your idea about it. Eventually, Hui K’e received transmission and became the Second Patriarch in China.

Another point is how Bodhidharma’s teaching embodies our Zen traditions by pointing directly to the truth. Here is a four-line stanza that is attributed to Bodhidharma as a definition of Zen:

A special transmission outside of the scriptures,

Not depending on words or letters,

Directly pointing to mind,

Seeing into one’s true nature and,

Attaining Buddhahood.

It is so straightforward — there’s no mucking about with these four lines. They are so clear that there can be no confusion. The dependence on scriptures during Emperor Wu’s time was fundamental in Buddhist practices. But the practice of reading sutras and attaching to the words intellectually misses the point entirely.

The whole point of Buddhism, the whole point of Zen, is to experience our true nature, and not to intellectualise what that might be.

Of course we read and study the scriptures. The point is to use our intellectual capacity, to use all of our capacities to naturally deepen in our experience. Bodhidharma asks us to go deeper: to bring the Ancestors’ teachings into our awareness, into our zazen, and into our moment-by-moment life activities. When reading a sutra, question the meaning of every passage by asking oneself, what does this mean? In the case of Sixth Patriarch’s awakening, what does – abiding nowhere, awakened mind arises – mean? This one simple phrase from The Diamond Sutra, what does it actually mean?

To focus one’s attention on the sutras in this way gets to the core of not only these sutras but also provides insight into the person reading them. The whole purpose for which they were preserved, generation after generation, was for the reader, or in the Sixth Patriarch’s case, for a listener, to align with the Ancestor’s teachings. To read them and just to think about them does not really get there. In a sense, there is no essence there because they are not yours. We have to find the key to them and make them our own, and in that way, we can pass these teachings on to others. The Dharma is alive and vibrant; yet it only flourishes when it is lived through and taught with our deep huge mind.

Bodhidharma’s teaching continues to guide us today, in particular, the work that Bodhidharma did on the Ten Grave Precepts. In Zen traditions, the Ten Grave Precepts are offered to both lay people and people who wish to ordain. Bodhidharma saw that precepts from the Theravada traditions were excessively long. Men who wish to ordain, are required to take 250 precepts while the women who wish to ordain, are required to take 500 precepts. On a personal note, when my teacher ordained me 33 years ago, he did what is customary in a public ceremony. He gave me the Ten Precepts along with the accompanying rituals. But that was just the first step. Later, he tossed a manila envelop at me with all the 500 precepts, and indicated that I was to read them alone. Traditionally, this reading was meant to be done in a group with other ordained people but apart from me, my teacher was the only ordained person present (and he was headed off to the movies), so I read them by myself.

And with deep respect for people who practice these 750 precepts in other traditions, I looked through these precepts for myself. I remember thinking these are just nit-picky codes of behaviour: don’t do this, don’t do that, do this, do that, and they go into miniscule detail. After awhile, I thought – okay, got it, and that was the end of it for me. The only thing that was meaningful to me was to recognise, as Bodhidharma and countless other people have that, without having seen one’s true nature, the 500 precepts were just words, just form. To attach to them in that way, to attach to them in any way, was missing an important point of the Ten Grave Precepts – that they are the essence of all the precepts.

Naturally, the Buddha taught the 750 precepts in a different time, in a different place, and based on different needs. However, Bodhidharma paired down the 750 precepts because the words, the nonstop words, were only being taught as forms. Precepts are an acknowledgment of and inspiration to spiritual awakening. You are allowed do this and not allowed to do that is dualism and does not get there. Bodhidharma encourages us to take our experience deeper. He did not operate at the level of form; Bodhidharma operated from this deep huge mind.

Bodhidharma has given us the Ten Grave Precepts that we use today. The precepts are about acknowledging and deepening in one’s spiritual awakening. It is not about, you have to do this or you have to do that. Precepts are yet another opportunity to purify one’s true state of mind, as one might work to clarify a seemingly elusive koan, and in this way experience the truth of our life. Rather than trying to squeeze one’s life into a conceptual framework, we work towards that already existing, but not yet experienced, huge deep state of mind that is before a single thought occurs. To work on the precepts in this way, one has a sense of how Bodhidharma intended us to bring these precepts into our awareness and to work with them through our experience; to go beyond all dualistic thought and to know that place of non-arising for one’s self. Then, of course, we have to go beyond that experience of non-arising in order to help others experience for themselves, this truly liberated and huge deep mind.

For our purposes today, I will read the 10 Grave Precepts out loud slowly, so that we can listen to the truth from which they are being offered:

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, to not kill life.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, to not consider anything as one's own.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, associations between two people should be open, pure and bright.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, true words and true mind are the base of attaining the way.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not delude the true self.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not point out other's faults and mistakes.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not praise yourself and degrade others.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not be possessive with the Dharma Treasures.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not indulge in anger.

- From the most clear, profound and subtle mind, do not dishonour the Buddha, the Dharma or the Sangha.

When we consider the First Precept, which is perhaps the most important – from the most clear, profound and subtle mind, to not kill life – this precept is the actualisation of our deepest state of mind. No one needs to tell us not to kill but we attach to our thoughts and we kill anyway. If we work on this precept then our lives will naturally align in a harmonious and authentic way of being. Then, we can experience for ourselves what the Ancestors are saying – that all life holds every value, of every single thing, in the entire universe. That’s the truth and in that truth there is no me, or my. And this is Bodhidharma’s point, for each of us to experience the truth, and not get stuck on our personal dietary dilemmas or in our ethical belief systems; to not get stuck in any thing. This is how Bodhidharma is teaching us to uphold and to use all the precepts - to clarify our own mind so that we can know the truth of all of them, all 750 precepts, for ourselves. Only then can our actions benefit all beings. This is a very important point.

As previously stated, Bodhidharma travelled to China from India and eventually gave transmission to Hui K’e, who became the Second Ancestor in the Zen lineage in China. Dharma roots are now being sunk down into Australia, cultivated by people such as this group at Khacho Yulo Ling Buddhist Centre. All over Australia, this slow and meticulous process of transmitting the Dharma is happening. And as for Bodhidharma, our work is set out before us. If we put down roots and the plant is carefully cultivated, it will flourish. The Dharma caretakers must cultivate the roots of Dharma by continuously clarifying and purifying their own minds. If we tend to our practice diligently, with sincere, honest and truthful efforts, the Dharma will flourish.

This is what is on the line here. This is what is most important. We must see what direction our zazen is taking us in so that we can observe for ourselves, whether we are cultivating a correct and clear way of being. This is what this retreat here today is all about – to bring all of our efforts together into a single point and focus everything into our zazen. Every effort that is put forth here today is part of our historic but real-time Dharma transmission from the Asia to Australia.

And for that, I thank you.